The "Second Product" Trap: When to Expand Your Product Line

Your first product is flying off the shelves, investors are purring, and you're feeling rather smug. Naturally, your next brilliant move is to launch product number two. Because nothing says "sustainable success" quite like immediately complicating everything that's working perfectly well, right?

Siren Song of the Second Product: When Diversification Is Strategy and When It's Self-Sabotage

The pitch meeting where you first describe your second product idea is the business equivalent of the morning after a night out, texting your ex. It feels brilliant in the moment. Revolutionary, even. But is it really the strategic masterpiece you've convinced yourself it is, or just another spectacular way to set fire to your remaining runway? (And deep down, you already know the answer, don't you?)

The Second Product Delusion: Why We're All So Eager to Complicate Our Lives

There's something irresistibly seductive about the second product. Your first offering has found its footing—or at least stopped actively haemorrhaging money—and suddenly you're eyeing new horizons like a sailor who's forgotten how seasick they were on the last voyage. I understand the impulse. The first product feels... solved. The challenges have become familiar, even comfortable. The new idea, meanwhile, sparkles with possibility and none of the tedious realities of execution.

But here's what we're actually doing: we're mistaking boredom for completion. We're conflating our personal desire for novelty with actual market opportunity. And most dangerously, we're often running away from the hard work of truly scaling what's already working.

Having watched my own carefully crafted business plans crumble under the weight of overambition, I've developed a healthy scepticism for the "obvious next step" that somehow always involves building something entirely new rather than maximising what you've already got.

The Hard Truth: Most Companies Aren't Ready for a Second Product

Let's be brutally honest: most startups should be focusing on making their first product truly exceptional before even contemplating a second. The signs that you're not ready are everywhere, if you're willing to see them:

Your first product isn't consistently generating predictable revenue. Your customer service team (which might just be you in a different hat) is still putting out fires daily. Your existing users are requesting features you haven't built yet. Your pricing still causes you to break out in a cold sweat during sales calls. Your marketing is still more guesswork than science.

And yet, there you are, sketching out product number two on the back of a napkin, convinced that this is the missing piece.

The hard truth I had to swallow after watching my own business aspirations smash against the rocks of reality: a second product won't fix a first product that isn't working. It will simply give you two underperforming products instead of one.

When a Second Product Actually Makes Sense (It's Rarer Than You Think)

Let's be clear—there are legitimate reasons to expand your product line. But they're specific, strategic, and frankly, less common than we'd like to believe:

- Your first product has reached demonstrable maturity—not just "we're no longer in crisis mode" but actual, boring stability.

- You've identified a genuine adjacent need among your existing customers (not a shiny new market you fancy conquering).

- The second product creates meaningful synergy with the first, strengthening your core value proposition.

- You have the resources to build it properly without neglecting your first product.

- The opportunity cost has been thoroughly examined—what else could you do with those resources?

I once convinced myself my struggling candle business needed an entire home fragrance line before I'd even mastered consistent production of the initial products. The result? Predictable disaster. I stretched my attention, diluted my brand, confused my customers, and watched my cash reserves evaporate faster than the essential oils I was suddenly importing from three different countries.

The Questions You're Avoiding (But Shouldn't Be)

Before you commit to that second product, force yourself to answer these uncomfortable questions with brutal honesty:

- Has your first product genuinely reached its growth ceiling, or are you just bored with it?

- Is customer acquisition for your first product truly optimised, or are you using product development as an excuse to avoid marketing?

- Have you exhausted all possible improvements to your existing product that could drive more value?

- Are your existing customers actively asking for this second product, or is this just your assumption?

- What specific capabilities have you built that make you uniquely qualified to deliver this second offering?

If you squirmed even slightly while reading those questions, you already have your answer. The second product isn't the answer—at least not yet. As research from achieving product-market fit consistently shows, the best way to validate an idea is when "money changes hands"—proving real-world demand beyond theoretical appeal. If your first product isn't generating that consistent exchange, a second won't magically solve the problem.

The Hidden Cost of Product Proliferation

What makes the second product particularly dangerous is that we systematically underestimate what it will take to execute well. We've forgotten the painful lessons of the first product—how everything took twice as long and cost three times as much as expected.

The invisible costs are even more insidious:

- The cognitive load of context-switching between multiple products and their unique challenges.

- The brand confusion when customers aren't sure what you stand for anymore.

- The organisational complexity of maintaining multiple product lines with different requirements.

- The inevitable resource fights between the established product and the new shiny object.

- The dilution of focus at precisely the time when doubling down might yield better returns.

Having learned these lessons through the expensive tuition of failure, I now view product expansion with healthy scepticism. It's not that it can't work—many great companies have multiple successful products. It's that the timing is absolutely critical, and most of us get it spectacularly wrong.

How to Actually Know When You're Ready

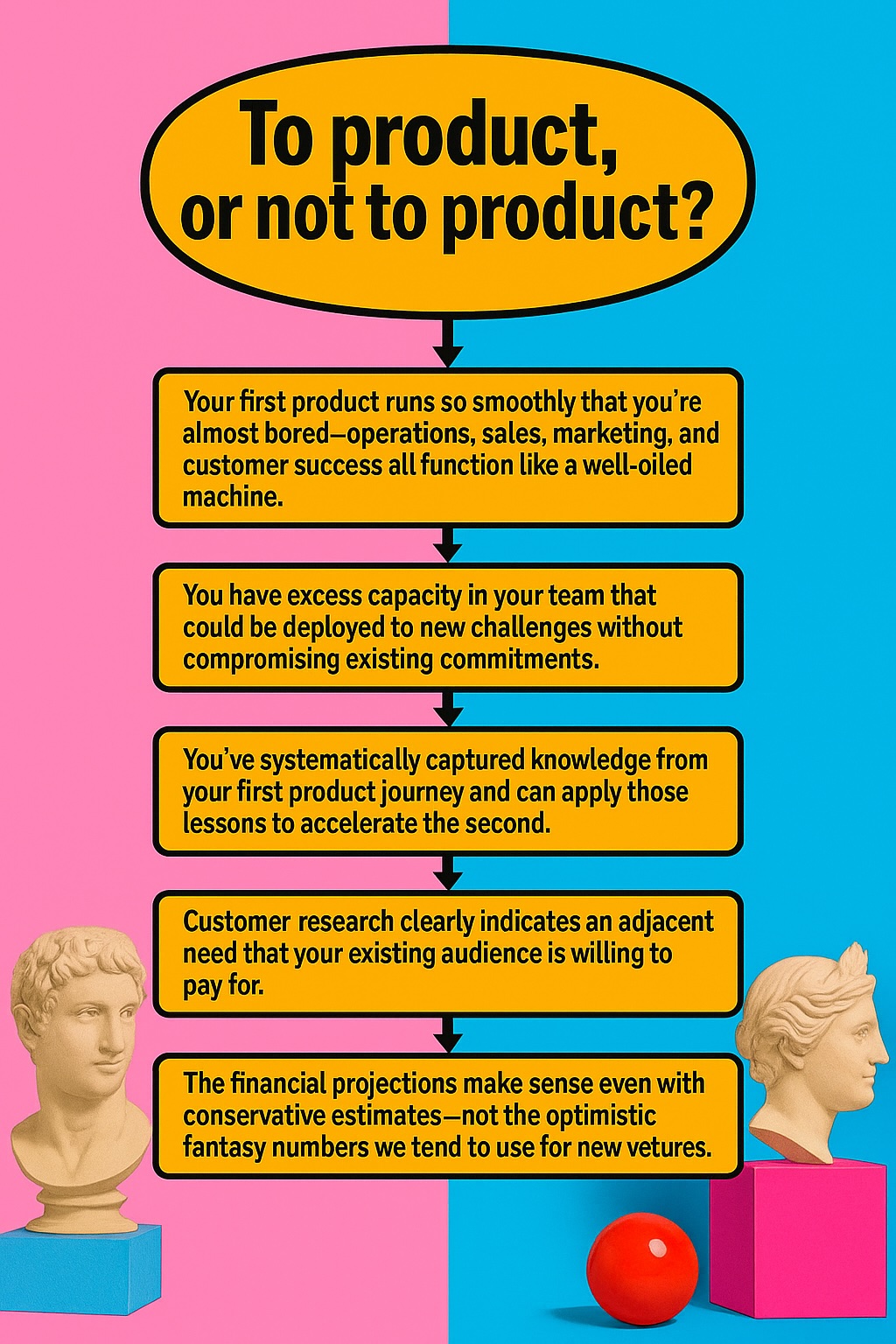

If you're still convinced a second product belongs in your future, here are the genuine signs of readiness:

- Your first product runs so smoothly that you're almost bored—operations, sales, marketing, and customer success all function like a well-oiled machine.

- You have excess capacity in your team that could be deployed to new challenges without compromising existing commitments.

- You've systematically captured knowledge from your first product journey and can apply those lessons to accelerate the second.

- Customer research clearly indicates an adjacent need that your existing audience is willing to pay for.

- The financial projections make sense even with conservative estimates—not the optimistic fantasy numbers we tend to use for new ventures.

The most reliable test? If you were to drop dead tomorrow (cheerful thought, I know), would your first product continue to thrive without your constant attention? If the answer is no, you're not ready for a second act. As Marc Andreessen notes in his insights on what comes after product-market fit, early adopters represent only 5% of the total market, leaving 95% for competitors to capture—but only if you've truly mastered serving that initial segment first.

The Strategic Alternative: Go Deeper, Not Broader

Instead of building an entirely new product, consider the underexplored potential of what you already have:

- Could you create premium tiers or professional versions of your existing product?

- Are there untapped market segments that could use your current offering with minimal adjustments?

- Could you extend your product's functionality in ways that increase its value to existing customers?

- Is there potential to create complementary services around your product rather than new products?

- Could strategic partnerships deliver new value to your customers without the overhead of building something new?

When my own business was struggling, I mistakenly thought diversification was the answer. What I should have done was perfect my core offering, strengthen operations, and build deeper customer relationships before attempting to conquer new territory. Understanding your customers' true pain points is crucial—customer pain points fall into four main categories (Service, Product, Process, and Emotional), and addressing these systematically in your existing product often yields better returns than building something entirely new.

When to Ignore This Advice (Because Sometimes You Should)

There are legitimate exceptions to every rule, including this one:

- If your first product is clearly hitting fundamental market limitations that cannot be overcome.

- If dramatic industry changes have made your primary offering obsolete or uncompetitive.

- If you've received clear, repeated signals from your customer base that they need something you're not providing.

- If a competitor is about to enter your space with a superior offering and you need to pivot.

- If you've genuinely mastered your first product category and have the resources to expand without compromise.

The key distinction is whether you're expanding from a position of strength or using the second product as an escape hatch from the challenges of the first. Be ruthlessly honest with yourself about which category you fall into. Research from a16z on navigating markets that don't yet exist reveals that most startups fall into the chasm between early adopters and mainstream users instead of successfully crossing it—even the most magical products can suffer from years of little or no growth before taking off.

The Decision Framework: When in Doubt, Don't

If you're on the fence about launching a second product, here's my battle-tested approach:

- Default to "no" unless there's overwhelming evidence for "yes"—the burden of proof should be on the new product.

- Test minimally viable versions with existing customers before building anything substantial.

- Establish clear success criteria beforehand—what specific results would justify continued investment?

- Set a financial ceiling for the experiment—how much are you willing to lose if it doesn't work?

- Create a "kill switch" decision point—a specific moment when you'll objectively evaluate whether to continue or abandon the effort.

I've found that forcing myself to articulate precisely why this second product deserves to exist often reveals the emotional rather than strategic motivations behind my thinking. And when emotions are driving product decisions, disaster usually follows close behind. The Lean Product Process framework provides a structured approach: the Product-Market Fit Pyramid consists of five layers (Target Customer, Underserved Needs, Value Proposition, Feature Set, and UX) that build on each other through continuous testing and refinement.

The second product isn't inherently wrong—it's just that the timing is usually wrong. And timing, as they say, is everything.

So before you dive headlong into that exciting new product development cycle, take a breath. Look at your first product with fresh eyes. Ask yourself whether you've truly exhausted its potential. Consider whether your resources might be better spent deepening rather than broadening. And remember that every successful multi-product company first became extremely good at one thing before attempting a second.

The siren song of the second product will always be there, tempting you toward the rocks. But unlike Odysseus, you don't need to tie yourself to the mast—you just need to recognise the song for what it is: a beautiful distraction from the less glamorous but ultimately more rewarding work of perfecting what you've already begun.