5 Questions to Ask to Determine if a Problem is Actually Worth Solving

Not every problem deserves your precious time and energy. Some are elaborate distractions masquerading as urgent crises. Before you roll up your sleeves and dive into solution mode, ask yourself these five questions to separate genuine challenges from time-wasting red herrings.

The Startup Sanity Checklist: Is Your "Brilliant Idea" Actually Worth the Next Three Years of Your Life?

Let's call a squid a squid—we founders have a peculiar affliction. We fall madly in love with problems that exactly no one else cares about. We'll spend months building solutions to issues that are merely mild inconveniences, convinced we're about to revolutionise an industry that's been ticking along quite nicely without our intervention.

The Expensive Art of Solving Imaginary Problems

The startup graveyard is littered with beautifully designed, impeccably engineered solutions to problems that weren't really problems at all. We've all been there, haven't we? That moment when you've built something so clever, so elegant, so bloody brilliant that surely the world will beat a path to your door—only to discover the world is quite content with the path it's already on.

Having learned from my own business mistakes, I now know that validating a problem is infinitely more important than perfecting a solution. After watching my cash flow evaporate while solving a "problem" that the market greeted with a collective shrug, I developed a ruthless filtering system. Because the truth is, not all problems are created equal, and not all are worth the inevitable grey hairs, sleepless nights, and strained relationships that come with building a business around them.

The Problem Worth Solving Litmus Test

Before you quit your job, remortgage your home, or alienate your loved ones by becoming a founder-shaped ghost, run your "world-changing idea" through this checklist. It's the brutal assessment I wish someone had forced me to take before I convinced myself that the world was desperately awaiting my contribution to the scented wax industry.

- Is this problem frequent enough that people encounter it regularly, or is it a once-in-a-blue-moon annoyance?

- Is it urgent enough that people actively seek solutions rather than just living with it?

- Is it expensive enough (in time, money, or emotional cost) that people would happily pay to make it go away?

- Is it unavoidable for your target customer, or just a niche issue affecting a tiny subset?

- Is your proposed solution at least 10x better than current alternatives (including doing nothing)?

If you're answering "not really" to more than one of these, you might be about to embark on a very expensive hobby rather than a viable business. And that's fine—if you're honest with yourself about it. Understanding the telltale signs of a genuinely good problem can save you from the heartbreak of building something nobody wants.

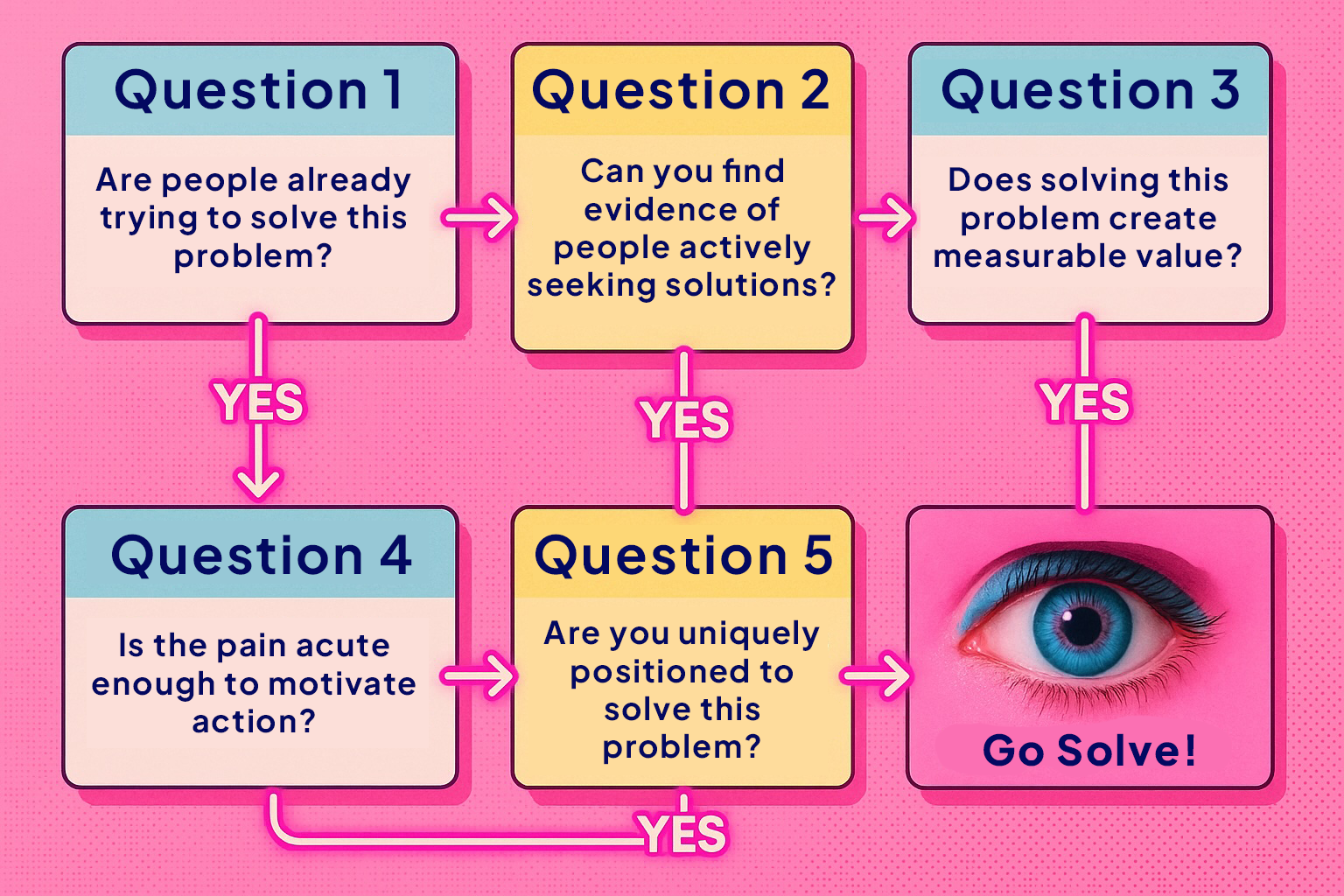

The Five Questions That Separate Gold Mines From Money Pits

Let's dig deeper into the questions that will save you from the special kind of heartbreak that comes from building something nobody wants. (A heartbreak I've experienced firsthand, complete with the 3 AM existential crises of "why did I think this would work?").

Question 1: Are people already trying to solve this problem?

Contrary to popular startup mythology, being first to market with a novel solution isn't always the advantage it's cracked up to be. If you're solving a problem nobody's addressed before, there's a non-zero chance it's because nobody actually cares enough to bother.

Look for DIY solutions, workarounds, hacks, and complaints. People MacGyvering solutions with duct tape and paperclips is a beautiful sign. It means they care enough about the problem to invest effort in solving it, but haven't found an elegant solution yet. That gap between caring and satisfaction is your opportunity.

The absence of competitors isn't always a good sign. It might mean you're a visionary seeing what others miss—or it might mean you're hallucinating a market. After experiencing burnout from trying to do everything alone in my previous venture, I've learned to appreciate competitors as validation that there's at least some market interest.

Question 2: Can you find evidence of people actively seeking solutions?

This is about demand signals—proof that people are motivated enough by this problem to take action. The strength of these signals directly correlates with how valuable the problem is.

- Search for Reddit threads where people discuss the problem—are they desperate or just mildly annoyed?

- Check Google search volumes for problem-related keywords (not solution-related).

- Look at community forums in your target industry—what problems come up repeatedly?

- Examine review complaints about existing solutions—what frustrates people most?

- Browse social media hashtags related to the problem—are people venting regularly?

The mistake I made with my homeware business wasn't just overestimating the problem—it was failing to notice that while people occasionally complained about candle selection, they weren't actively searching for solutions. They were perfectly content with their occasional Anthropologie splurge or TK Maxx bargain hunt. The "problem" lacked urgency. If you want to master using Reddit for product validation, it's essential to look beyond mere mentions and focus on genuine desperation.

Question 3: Does solving this problem create measurable value?

A problem worth solving should create value that can be quantified—in time saved, money earned, stress reduced, or status gained. The more precisely you can measure this value, the easier it will be to price your solution and communicate its worth.

For business problems, calculating ROI is straightforward: "Our solution saves procurement teams 15 hours per week, which translates to £2,000 monthly savings for a mid-sized company." For consumer problems, it's trickier but still possible: "Our app reduces the average time spent meal planning from 3 hours to 20 minutes per week."

If you struggle to articulate the value in concrete terms—"it's just better" or "it's more convenient"—warning bells should sound. I learned this when attempting to quantify the value of "discovering the perfect luxury candle." The answer was a humbling "nice to have" rather than "need to have."

Question 4: Is the pain acute enough to motivate action?

Human beings are remarkably adaptable creatures. We'll tolerate astonishing levels of inconvenience before we're motivated to change our behaviour. This inertia is your enemy as an entrepreneur.

Rate your problem on what I call the "Paracetamol Test":

- Mild Headache: Annoying but people live with it.

- Throbbing Headache: People actively seek relief but might delay if it's inconvenient.

- Migraine: People will pay almost anything, right now, to make it stop.

- Brain Tumour: Existential threat—solving it is non-negotiable regardless of cost.

If you're solving a "mild headache" problem, you're fighting an uphill battle against inertia. Your marketing costs will be astronomical because you'll need to convince people they should care about something they've successfully ignored until now.

After experiencing the glacial sales cycle that comes with "nice-to-have" products, I now aim exclusively for problems that rate at least a "throbbing headache" on this scale.

Question 5: Are you uniquely positioned to solve this problem?

This final question isn't about the problem itself but about you. Even the most valuable problem isn't worth your time if you lack the expertise, resources, or passion to create a substantially better solution than what exists.

Your unfair advantage could be:

- Technical expertise others lack

- Deep industry knowledge that provides insight

- Unique access to a customer segment

- Intellectual property or proprietary technology

- Experience with the problem that gives you empathy others miss

Without some edge, you're just another entrant in a race where others may have a head start. I've learned that being a generalist founder with "good taste" isn't enough—you need some specific leverage that makes your solution disproportionately excellent.

How to Actually Test Your Problem's Viability (Before Wasting a Year of Your Life)

Now that you've subjected your problem to merciless interrogation, it's time to gather evidence rather than just making educated guesses. Here's my battle-tested approach to market validation:

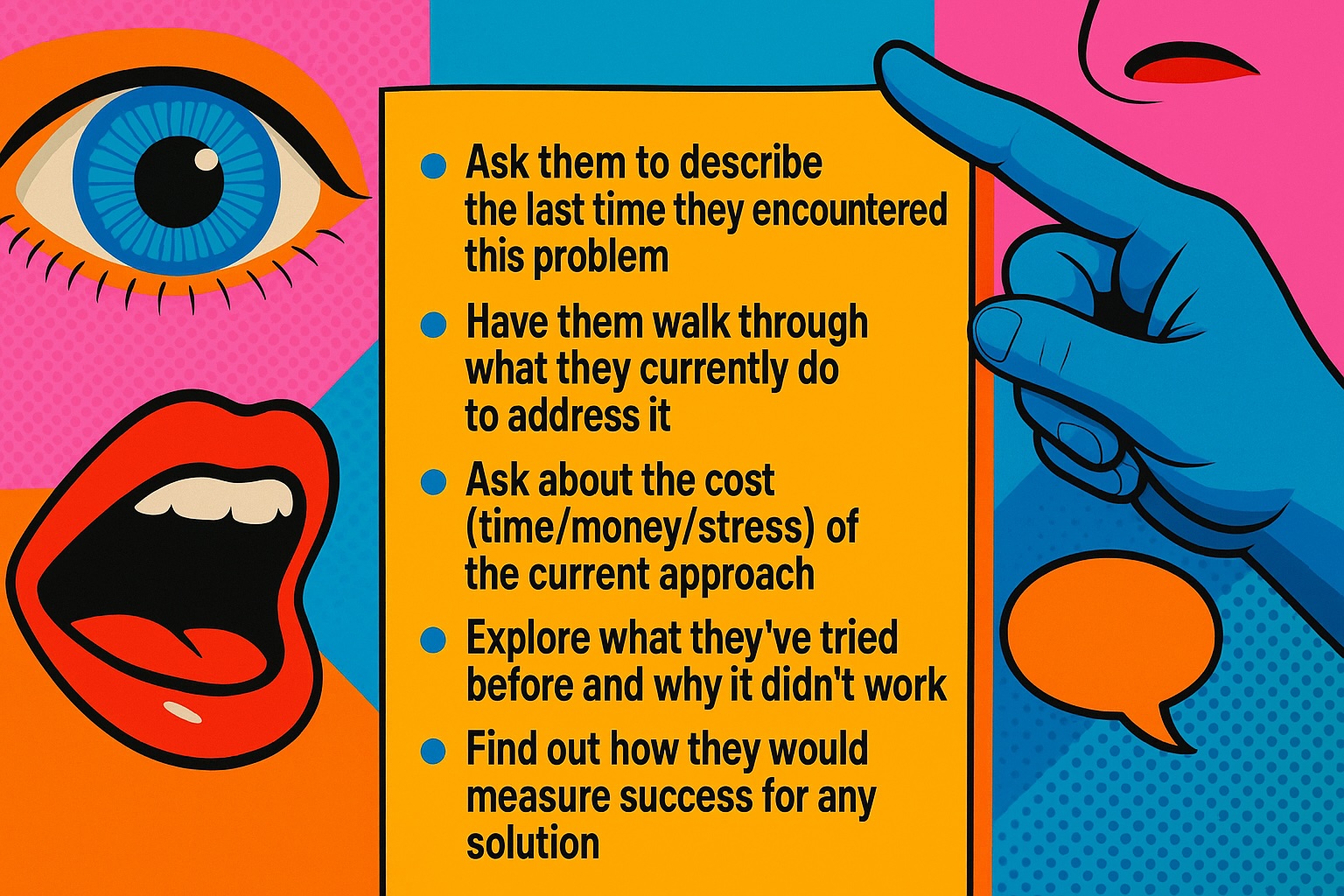

The Problem Interview Technique

Conduct at least 20 interviews with potential customers, but with a critical twist: don't mention your solution. The moment you describe your brilliant idea, human politeness kicks in and you'll get false positives. Founders frequently misdiagnose customer pain because they listen to what customers ask for (a feature) instead of understanding what they are trying to achieve (an outcome). The crucial insight is that customers are experts in their problems, but you are the expert in the solution—this distinction is key to avoiding a misdiagnosis and building something people truly need, as highlighted by Forbes.

Instead, focus exclusively on understanding the problem:

- Ask them to describe the last time they encountered this problem

- Have them walk through what they currently do to address it

- Ask about the cost (time/money/stress) of the current approach

- Explore what they've tried before and why it didn't work

- Find out how they would measure success for any solution

The gold in these interviews isn't when people say they have the problem—it's when they demonstrate they've already tried to solve it. Actions speak infinitely louder than hypothetical interest.

The Smoke Test: Sell Before You Build

The most brutal (and effective) validation technique is trying to collect money for a solution that doesn't exist yet. This sounds deceptive, but it's not if handled ethically.

Create a simple landing page describing the solution and its benefits. Include pricing and a prominent "Pre-order" or "Join Waitlist" button. When people click it, be honest: "We're still building this solution. Enter your email to get early access and a 50% discount when we launch."

Measure not just email sign-ups (a weak signal) but the conversion rate on your "buy" button (a strong signal). A 5%+ conversion rate from cold traffic suggests genuine interest. Anything below 1% is a warning sign.

Had I run this test before diving into inventory, manufacturing, and branding for my ill-fated homeware business, I would have saved myself significant capital and heartache. The truth is, while people liked the idea in theory, their behaviour revealed they weren't motivated enough to act.

The Concierge MVP: Solve It Manually First

For many problems, you can test the waters by delivering the solution manually before building technology. This approach lets you verify people will pay while refining your understanding of what they truly value.

Find five customers willing to pay you to solve their problem using whatever cobbled-together process you can manage. Yes, it won't scale. That's precisely the point—you're not trying to build a business yet; you're trying to confirm a business should be built at all.

This hands-on approach reveals nuances you'd never discover through interviews alone. You'll find that what customers say they want often differs from what they actually value when money changes hands. Understanding what product-market fit actually means becomes crucial at this stage, as it's the difference between a profitable business and an expensive hobby.

Conclusion: The Courage to Walk Away

The most valuable skill in entrepreneurship isn't perseverance—it's discernment. Knowing which problems deserve your limited time on this earth separates successful founders from the perpetually frustrated. Research shows that only 30% of people meet all three of their personal minimums for joy, achievement, and meaningfulness each week, and those who derive high subjective value from their work activities report life satisfaction scores of 4.2 out of 5. Even a 1.5-hour shift per day from low- to high-value activities can result in a significant increase in perceived life satisfaction, as detailed in MIT Sloan Review.

Sometimes the bravest decision you can make is walking away from a problem that fails these tests, even after you've invested time thinking about it. I've abandoned more ideas than I've pursued, and each abandonment hurt my ego but preserved my resources for battles worth fighting.

The question isn't whether you can solve a particular problem—clever, determined people can solve almost anything. The question is whether solving it matters enough to dedicate years of your life to the cause. Choose wisely, because while ideas are infinite, your time decidedly is not.